The History of the Order (12th - 13th Centuries)

Introduction

The history and lineage of today's Military and Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem (OSLJ) has and continues to be unclear and often disputed. The "geneological" examination of the Order has been challenging as history has focused primarily on the Knights Templars and/or the Knights Hospitallers due to the relatively minimal impact the Order of St. Lazarus has made on documentary sources, largely because of its exemption from many of the things that generally bring medieval religious orders to the attention of historians.[1] In addition, the questions on the origin of the order of St Lazarus is complicated by a shortage of documentary and archaeological material for almost all periods before 1500.[2] This lack of primary sources has the normally conservative Catholic Encyclopedia to comment that 'the historians of the order have done much to obscure the question of its origins by entangling it with gratuitous pretentions and suspicious documents'.[3] In addition, the uniqe features of the Order having a strange hybrid of a knightly, leprous and monastic order, sharing certain characteristics with the Hospitallers and others with the Templars has led historians to draw inaccurate or conflicting conclusions with respect to the OSLJ. However, with further historical research tapping into an expanded range of sources including documentary and archeological artefacts, more information can be pulled together than might ever have seemed possible in the first instances of research creating a more consistent and balanced picture.[4] This presentation of the history of the Order will include citations to known resources, papers, publications providing the best and most current understanding of its history at this time. As more details are learned, this presentation will be updated to reflect the new findings.

12th - 13th Centuries

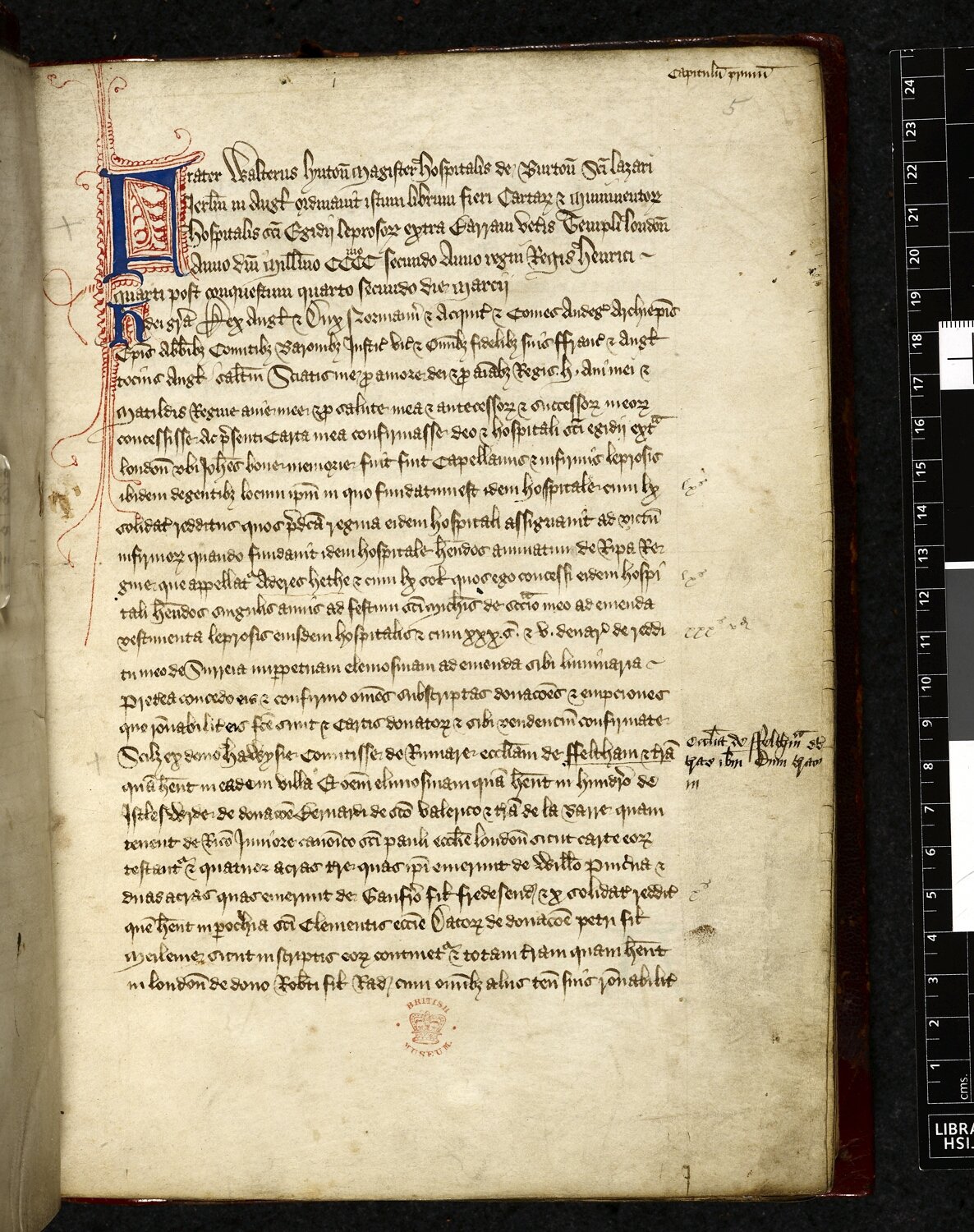

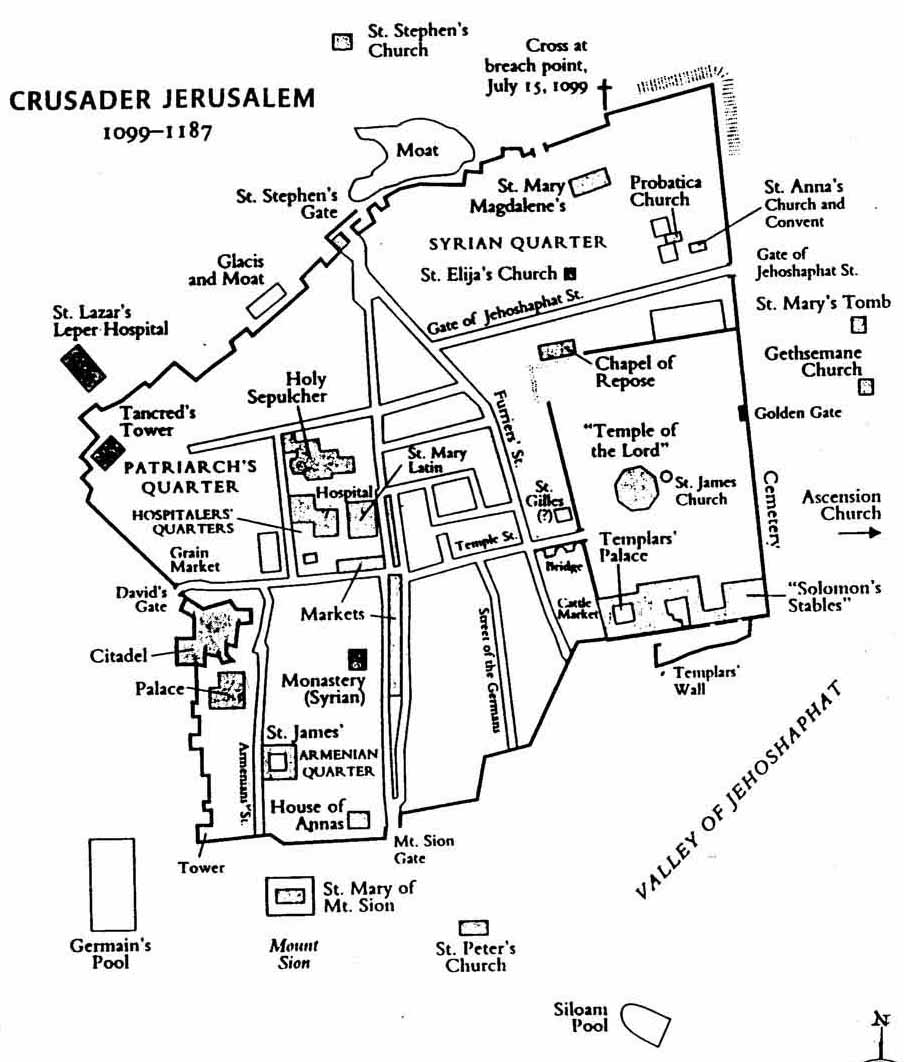

Direct links to the earlier leper hospitals established prior to the First Crusade with the Order of St. Lazarus remain doubtful at this time, therefore, this examination begins with the twelfth century. Presently, the best source for this early period is part of the order's Cartulary[5][24], containing about 40 charters providing a 'precise picture of this hospitaller institution'.[6] According to this source, the order established itself in the 1130s on a site outside the wall of Jerusalem in the area of the St. Lazarus postern between the Tower of Tancred and the Gate of the Column of Saint Stephen, through the first unambigious reference of a grant by King Fulk (1131-43) in 1142 giving land in Jerusalem to 'the church of St. Lazarus and the convent of the sick who are called miselli' (Map 1) [7]

This community consisted of leper brothers assisted by healthy counterparts and probably secular chaplains, living a life of abstinence and prayer, held meetings to make decisions and were presided over by a master, who was normally selected from amongst the lepers. [8] The "house of the lepers of Saint Lazarus" is described as being situated on the pilgrim route between the Mount of Olives and the Jordan being well positioned to gather alms and from which they might travel to bathe in the supposedly curative waters of the River Jordan. [9] The first master of the order whom the name survives is Bartholomew, who first appears in 1153. Barber has suggested that this Bartholomew may have been a Templar who left his order to reap the rewards of ministering to the sick. [10]

The work of the order grew in importance and visibility in the latter half of the twelfth century through increased donations and grants, including one in 1159 by Queen Melisende who granted the order a gastina called "Betana" specifically to sustain an additional leper beyond the existing complement suggesting that the support of the lepers in the kingdom was a growing and visible problem. [11] Further support of the growing momentum is supported by the late twelfth-century code of law known as the "Livre au Roi", which stated that a knight or sergeant who became leprus should join the Order of Saint Lazarus, "where it is established that people with such an illness should be." For the Knights Templar, there was an equally explicit provision: their Rule shows that leprous brothers could transfer to Saint Lazarus, athough they were not compelled to do so. [12] The knights of St John never made such a rule - it was assumed that they felt capable of looking after their own sick knights - and the Assises de la Cour de Bourgeois is also silent on the matter. [13] This draws us to the conclusion that the convent of St Lazarus, perhaps because of its aristrocratic connections, became regarded as a convenient receptable for leprous knights, especially those from among the Templars. [14]

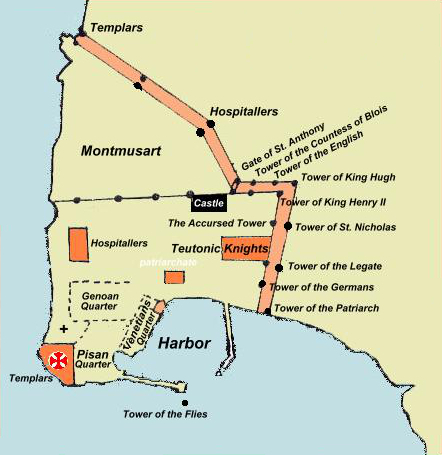

The connection with the Templars had become increasingly evident when the order, as well as other Latin institutions based in Jerusalem withdrew following the fall of the city of Jerusalem to Salah al-Din in 1187 and re-established themselves at Acre. [15] With the existence of a Gate of Saint Lazarus in Montmusard (a northern suburb within Acre), which is attested by "the Templar of Tyre,", who knew the late thirteenth-century city well, and by early fourteenth-century maps, reinforces the case for believing that the order established itself there quite soon after 1187. [16] Sometime between 1198 and 1212 and later again in the 1250's, the defenses of Acre had been greatly strenghtened by the buiding of a new outer wall around the city's landward side. This involved erecting a double line around the growing suburb of Montmusard, which had previously been too insignificant for such defenses. [17] In 1258, during the civil disturbances known as the War of St Sabas, the master of the Temple, Thomas Bérard, took refuge in the tower of St Lazarus when his own stronghold was subjected to crossfire between the Pisans, Genoese and Venetians, and in 1260 it was made compulsory for a leprous Templar to enter the order of St Lazarus. [18] Its expanded military role was clarified by the mid-thirteenth century. In 1234, Pope Gregory IX (1227-41) appealed for aid to help the order pay off its debts contracted in 'defence of the Holy Land', and in 125, Pope Alexander IV (1254-61) spoke of 'a convent of nobles, of active knights and others both healthy and leprous, for the purpose of driving out the enemies of the Christian name.' [19] Although the idea of leper knights might seem bizarre, given the circumstances of the military and spiritual needs of the Latin kingdom and chronic shortage of manpower, it made perfect sense to exploit the skills of trained fighting men, regardless of their physical condition, essentially forming the last line of defence for the Christians of the Latin East. Historical accounts do not paint a notably successful collection of warriors, where a string of military failures involving the knights of the order of St. Lazarus including a report that 'all the leper knights of the house of st. Lazarus were killed'. and during the crusade of Loius IX (1248-54) knights of the order were present at the disaster at Marsuna in 1250. [20] Although, there are no accounts uncovered yet, it is possible that rather than fighting with the main body of troops, they undertook a foraging or scouting role, which would have distanced them from the troops thus minimizing the spread of infection. However, later in the thirteenth century, when Sultan Khalil of Cairo besieged the city in 1291, the order of St Lazarus was able to muster a force of 25 knights. [21] On the night of 15/16 April a foray was made out of the St Lazarus Gate under William de Beaujeu, master of the Temple, to attempt to destroy the seige engines of the enemy, but the crusader force, which probably included troups of the order, came to grief when their horses tripped over the tent ropes of their opponents in the dark. [22] After a bitter siege the sultan ordered the final assault on 14 May, and Acre fell amidst scenes of unprecedented carnage. All of the knights of St Lazarus perished. [23]

- Marcombe, David. "Leper Knights - The Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem in England, c.1150-1544". Boydell Press. 2004. ISBN: 978 1 84383 067 2. p.xviii.

- K.P. Jankrift, 'Die Leprosenbruderschaft des Heiligen Lazarus zu Jersalum un ihre Ältesien Statuten', in G. Melville (ed.), De Ordine Vitae: zu Normvorstellungen, Organisationsformen und Schriftgebrauch im mittelalterlichen Ordenswesen, Vita Regularis, 1 (Münster, 1996). pp.22-7.

- C.G.Herbermann et al. (eds), The Catholic Encyclopedia, 9 (London, 1910), p.97. Last accessed: Sep 11, 2015.

- S. Shahar, 'Des lépreux pas comme les autres. L'ordre de Saint-Lazare dans le royaume latin de Jérusalem', Revue Historique, 541 (January-March 1982), pp. 19-41; J. Walker, 'The Patronage of the Templars and the Order of St Lazaurs in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries', University of St. Andrews, Ph.D. thesis (1990); M. Barber, "The Order of Saint Lazarus and the Crusades', The Catholic Historical Review, 80, no. 3 (July 1994), pp. 439-56; K.P. Jankrift, Leprose als Streiter Gottes: institutionalisierung und organisation des ordens vom Heiligen Lazarus zu Jerusalem von seinen anfängen bis zum jahre 1350, Vita Regularis, 4 (M¨nster, 1996); K.P. Jankrift, 'Die Leprosenbruderschaft des Heiligan Lazarus zu Jersalem und ihre Ältesien Statuten', in G. Melville (ed.),De Ordine Vitae; zu Normvrstellungen, Organisationsformen und Schriftgebrauch im mittelalterlichen Ordenswesen, Vita Regularis, 1 (M¨s;nster, 1996), pp. 341-60; R. Hyacinthe, 'L'Ordre militaire et hospitalier de Saint-Lazare de Jérusalem en Occident; historier - iconographie - archéologie', University of Paris (Sorbonne), Ph.D thesis (2000); R. Hyacinthe, 'L'Ordre militaire et hospitalier de Saint-Lazare de Jérusalem aux douzième et treiziè siècles', in Utiles est Lapis in Structura: méanges offerts à Léon Pressouyre, Comité de Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques (Paris, 2000), pp. 185-93.

- British Library, record Harley 4015: Cartulary made for Walter Lynton, master of the hospital of the Virgin Mary and Lazarus, Burton Lazare, Leicestershire, 1402. The manuscript contains 214 folios (+ 3 unfoliated paper and 1 parchement flyleaves at the beginning + 3 unfoliated parchment and 2 paper flyleaves at the end) in the form of a parchment codex. The cartulary is arranged in sections by parishes, which are listed on ff. 2v-3, and includes copies of royal charters from the reign of king Richard I onwards (ff. 206-211). Last accessed: September 20, 2015.

- Hyacinthe, 'Saint-Lazare'. p. 186. The Cartulary is printed in A. de Marsy (ed.), 'Fragment d'un Cartulaire de l'Ordre de Saint-Lazare en Terre Sainte', in Archives de l'Orient Latin, 2 (Paris, 1884, reprinted New York, 1978), pp. 121-57.

- Marcombe, David. "Leper Knights - The Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem in England, c.1150-1544". Boydell Press. 2004. ISBN: 978 1 84383 067 2. p. 7.; J. Williamson, J. Hill and W.F.Ryan (eds), Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099-1185, Hakluyt Society, 167 (1988), p.143.

- Hyacinthe, 'Saint-Lazare', p. 186; Barber, 'St Lazarus', pp. 444-6; Shahar, 'Lépreux', pp. 27-9; Jankrift, Leprose, pp. 58-9.

- M. Barber. 'The Order of Saint Lazarus and the Crusades'. The Catholic Historical Review, 80, no.3 (July 1993). p. 450.

- Ibid, pp. 440-1.

- Ibid, p. 444.; "Fragment," no. XVI, p.135. The exact nature of the gastina is not clear, but it was probably a piece of uncultivated land dependent upon the villages of Magna Mahumeria and Parva Mahumeria, just to the north of Jerusalem, which were settlements colonized by the Franks. It seems that the order was expected to develop or redevelop the land. On the ambiguity of the term, see Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jersalem, 1174-1277 (London, 1973), pp. 43-44.

- Ibid, p. 444.; "Le Livre au Roi," in RHCr., Lois, Vol. 1 (Paris, 1841), pp. 636-637. A woman whose husband had entered a monastery was expected to lead a chaste life thereafter, usually in an appropriate religious hosue. However, since there was a prevalent belief that women could transmit the disease through sexual intercourse, the provisino that she enter a convent may have had added importance for contemporaries in these cases. In the twelfth century, leprosy in the Kingdom of Jerusalem seems to have been regarded as a male disease, there being no known provision for leprous women. The difference in the treatment of men and women is underlined by the case of the Burgundian knight who, in c. 1130, entered the Temple after his wife had contracted leprosy, leaving her and his daughters in the case of a local monastic house at Dijon, Cartulaire général de l'ordre de Temple 1119?-1150, ed. Marquis d'Albon (Paris, 1913), no. XXVII, p.19. This charter says much about contemporary confusion regarding leprosy, since his wife's ailment was no barrier to the knight's entry into the Temple.

- Marcombe, David. "Leper Knights - The Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem in England, c.1150-1544". Boydell Press. 2004. ISBN: 978 1 84383 067 2. p.11.; A.A.Beugnot (ed.),'Assises e la Cour de Bourgeois', Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Lois, 2 (Paris, 1843), p.38. Though the hospital of St John did not accept lepers, the case of the leper knights may have been different. Riley-Smith, Hospitallers, p. 22.

- Ibid, p.11.; The problem of leprous members of religious orders was common enough and not confined to the Latin East. For cases involving the English Franciscans (1392) and Bridgettines (1487), see CPapR Letters 4, 1362-1404, p.454; 15, 1484-92, p.42.

- M. Barber. 'The Order of Saint Lazarus and the Crusades'. The Catholic Historical Review, 80, no.3 (July 1993). pp. 447.; Saladin allowed ten Hospitallers to stay for up to a year to tend the sick, Cart, Vol. 1, no. 847, p. 527. It is likely that the same privilege was extended to the Order of Saint Lazarus.

- Ibid, p.448,; David Jacoby, "Montmusard, Suburb of Crusader Acre: The First Stage of its Development.", in Outremer, studies in the History of the Crusading Kingdom of Jerusalem presented to Joshua Prawer, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar, Hans E. Mayer and Raymond C. Smail (Jerusalem, 1982), pp. 205-217.

- Ibid, p.447.; Gestes des Chiprois, ed. Gaston Raynaud (Geneva, 1887), p. 245. See also the maps of Marino Sanudo (probably by Pietro Vesconte) and Paolino Veneto, Bernard Dichter, The Maps of Acre, An Historical Geography (Acre, 1973), pp. 17-18, 22-30.

- Marcombe, David. "Leper Knights - The Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem in England, c.1150-1544". Boydell Press. 2004. ISBN: 978 1 84383 067 2. p.11.; M. Barber. 'The Order of Saint Lazarus and the Crusades'. The Catholic Historical Review, 80, no.3 (July 1993). pp. 451.; S. Shahar, 'Des lépreux pas comme l'autres. L'Ordre de Saint-Lazare dans le royaume latin de Jérusalem', Revue Historique, p. 26.; K.P. Jankrift, 'Die Leprosenbruderschaft des Heiligen Lazarus zu Jersalum un ihre Ältesien Statuten', in G. Melville (ed.), De Ordine Vitae: zu Normvorstellungen, Organisationsformen und Schriftgebrauch im mittelalterlichen Ordenswesen, Vita Regularis, 1 (Münster, 1996). p.79.

- Ibid, p. 12.; L. Auvray (ed.), Les Registres de Grégoire IX, 1, BÉFAR, series 2 (Paris, 1896), p. 942; C. Bourel, J. de Loye, P. de Cenival and A. Coulon (eds), Les Registres d'Alexandre IV,, 1, BÉFAR, series 2 (Paris , 1902), p. 122.

- Ibid, p. 14.; G. Scalia (ed.), Salimbene de Adam, Cronica, 1 (Bari, 1966), p.255; Luard, Chronica Majora, 5, p.196.

- Ibid, p. 15.; This was not much fewer than the Templars and Hospitallers, who were estimated to have about 30 knights each at Acre. However, the two larger orders had more knights spread around outlying garrisons since their commitments were greater than those of the Lazarites. P. Bertrand de la Grassière, L'Ordre Militaire et Hospitaler de Saint-Lazare de Jérusalem, (Paris, 1960), p.21; D. Seward, The Monks of War: the military religious orders (London, 1972), p.81.

- Ibid, p. 15.; Seward, Monks of War, p.82.

- Ibid, p. 15.; Seward, Monks of War, p.84.

- Savona-Ventura, Charles. "The History of the Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem" Nova Science Publishers, Inc. NY. 2014. ISBN: 978-62948-563-8. pp. 14-15.